Garmisch-Partenkirchen

The history of the Partnach Gorge

Feel the magic in the unique nature

INTERESTING FACTS ABOUT THE GORGE

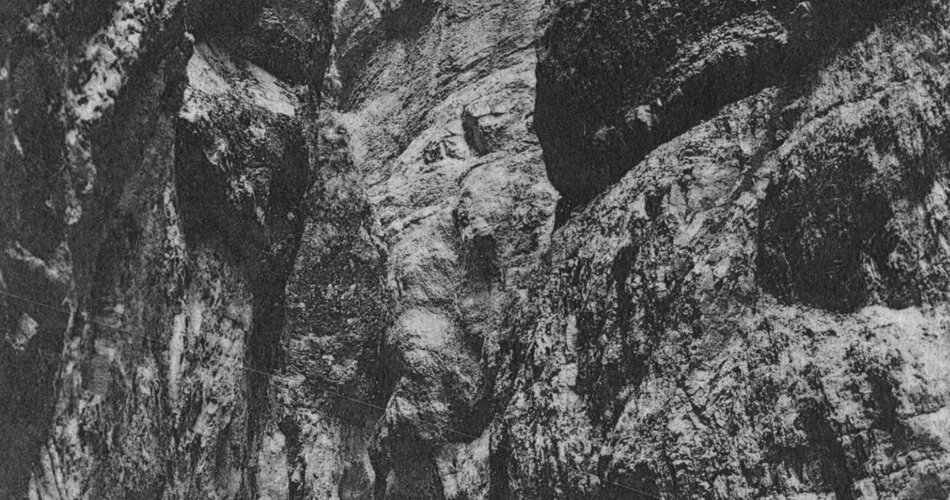

The formation of a gorge is just as extraordinary as experiencing it up close. Several million years ago, meltwater and debris hollowed out the hard rock.

What remained was a narrow gorge - the Partnachklamm in Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

However, the gorge, which was declared a natural monument in 1912, was not always so tame and approachable. In 1820, Josef Naus had to bypass the gorge on his first ascent of the Zugspitze.

still had to bypass the gorge. Today, two safe paths lead through it.

And once you are there, you will be captivated by its wild waterfalls, rapids and pools.

Before the Ice Age, the Partnach still flowed eastwards in the valley of today's Ferchenbach, found its way via Klais and Krün and flowed into the Isar there. Geologists assume that a bar of shell limestone near Graseck blocked the way into the Loisach Valley back then - only a rivulet led in the current direction of the Partnach. Over time, this rivulet dug deeper into the rock and created a pre-formed bed into which the Partnach broke and, over the course of thousands of years, created the layers of rock and the shape of today's gorge.

The source of the Partnach lies in the Reintal valley, which is one of the most beautiful high valleys in the Northern Limestone Alps. From here, the Partnach, a natural outlet of the Schneeferner - the remnant of an ice-age glacier on the Zugspitzplatt - carries its icy waters through the romantic Reintal valley. After the Partnach has passed the Reintalangerhütte and before it takes an underground course for a few hundred meters in the "Steingerümpel", it plunges steeply into the depths in the Partnachfall. At the Bockhütte, it flows through the Hinterklamm and Mittelklamm gorges, neither of which are accessible. Shortly before entering the Partnachklamm gorge, it gets a lot of water.

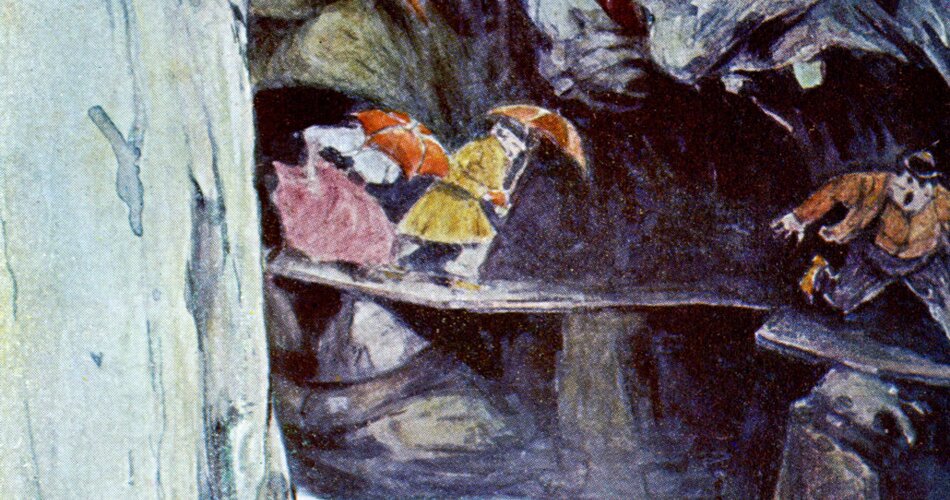

The Partnach Gorge gained great economic importance when the forest clearing of firewood and timber from the Ferchental, Reintal and Stuiben areas was permitted by the bishops of Freising and had to be transported - drifted - through the gorge into the valley.

The water wood, as it was called in contrast to the mountain wood transported by horse-drawn sledge, was drifted in spring, as the watercourse is at its strongest at this time due to the melting snow. For this purpose, the tree trunks were sawn to a length of one meter after felling, thrown into the Partnach and Ferchenbach rivers and floated down the valley. If the logs were pushed up against the rocks or became wedged together, the woodworkers had to risk their lives to get the logs moving again using so-called Grieshaken. To do this, they were roped down into the gorge from the very top on a kind of chair with a small roof to protect them from falling rocks.

The logs were then lowered into a side arm that had been created by a sluice at the wood stove on the upper Partnach bridge and led into a partially submerged sandy area. There, the logs were pulled ashore, stacked and measured by the forestry officials.

This hard and dangerous work was carried out until the beginning of the 1960s. After that, the Reintal and its side valleys were opened up by large forest roads on which the logs could be transported down the valley. Today, only the names "Triftstraße" and "Am Holzofen" are reminiscent of the logging in the Partnachklamm gorge and the "Kohlstattstraße" is a reminder of the charcoal kiln that once existed at the Triftplatz. Charcoal burners produced charcoal in kilns here.

Incidentally, an economic use of the Partnach and its alpine tributaries of a completely different kind was seriously considered in 1949. At that time, a plan was drawn up to build a 110-metre-high dam at the upper entrance to the Partnach Gorge, which would have created a huge reservoir from the entire front Reintal and Ferchenbachtal valleys. A power station in Wildenau would then produce electricity for the Bavarian power supply. There was massive opposition to this major project and it was never realized.

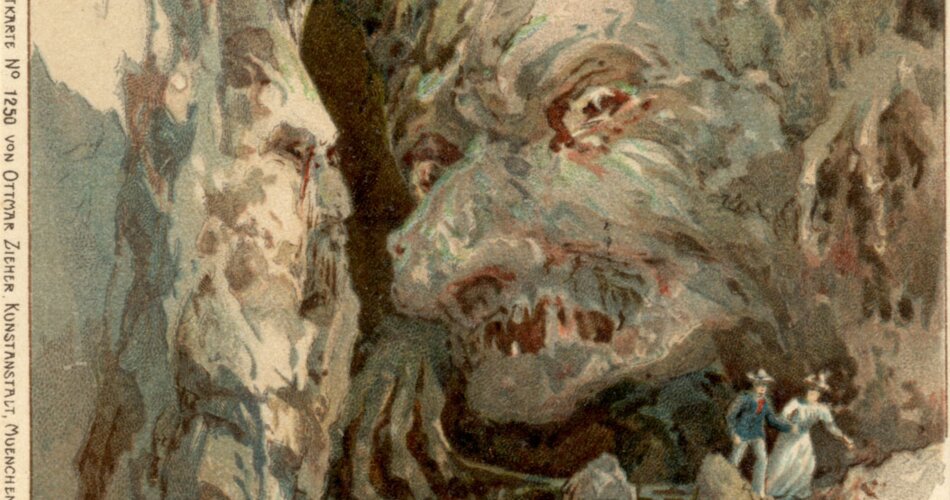

From 1910 to 1912, the Partnach Gorge, which was up to 80 meters deep, was developed for tourism under the most difficult conditions and at great financial expense. A devastating windfall in the forests of the Partnach and Ferchen valleys and the Schachen area above the Reintal valley in 1885 paved the way for the development in the truest sense of the word. At that time, the first efforts were already being made to construct footbridges through the inaccessible Partnach Gorge in order to make it easier to drive up. In 1886, a makeshift passage was created by installing iron girders in the steep rock faces just above the river, which were covered with wooden planks. The timber workers stood on this drift path and steered the logs drifting through the gorge with their gravel hooks. Remains of the former drift system can still be seen today. Until then, the dangerous Triftsteig was mainly used by hunters and forestry workers.

However, as tourism continued to grow, more and more adventurous tourists discovered the Partnach Gorge, which is why it was opened up to visitors as a natural monument in 1912. In 1930, it also became accessible in winter, making the spectacular ice formations in the winter gorge accessible. Today, the Partnachklamm is one of the most impressive gorges in the Bavarian Alps, attracting more than 200,000 visitors every year.

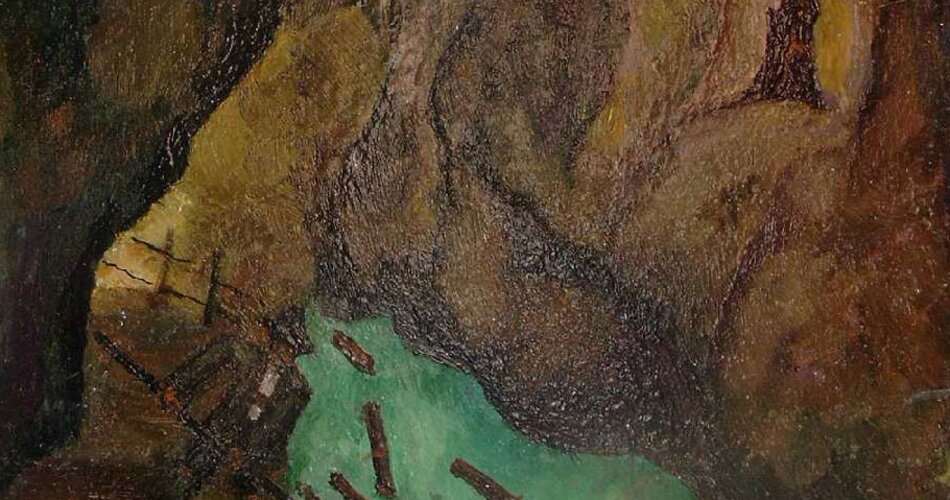

On June 1, 1991, approx. 5,000 m³ of rock broke out of a rock face at the southern end of the gorge and blocked the previous path and the course of the water. Fortunately, no people were injured. The rockfall created a small, natural reservoir and the Partnach Gorge carved its way through the huge boulders. Since 1992, a 108-metre-long tunnel blasted into the rock has led past the rock masses and the reservoir, providing a completely safe view of this natural phenomenon through windows.

Extensive construction work has made the Partnach Gorge even safer for visitors. For example, a previously 67-centimetre-wide section of the path has been widened to 1.20 and 1.40 meters respectively and thus alleviated a bottleneck for visitors walking in opposite directions. Rock stabilization and flood protection measures were also implemented.

Emergency call pillars and a total of 26 additional lights also ensure an attractive nature experience with high safety standards.